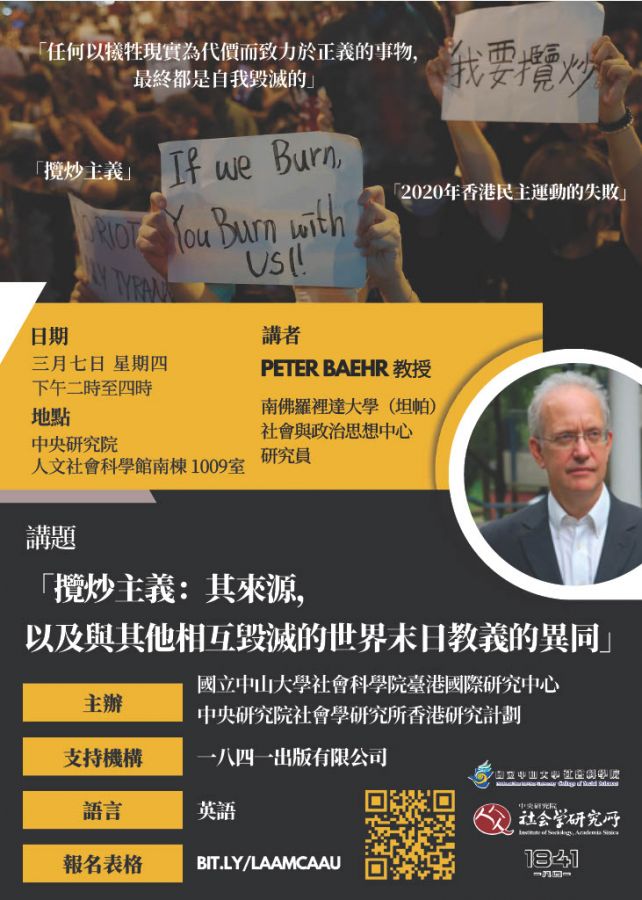

中研院社會所3/7「攬炒主義:其來源,以及與其他相互毀滅的世界末日教義的異同」演講

2024-03-06

中研院社會所「香港主題研究」小組邀請國際學者Peter Baehr教授來所演講,歡迎踴躍報名參加!

【講題】:攬炒主義:其來源,以及與其他相互毀滅的世界末日教義的異同

【講者】:Peter Baehr教授(Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa))

【主持】:梁啟智(本所訪問學人)

【時間】:2024年3月7日 14:00-16:00

【地點】:本所1009會議室(中研院人文社會科學館南棟10樓)

【報名連結】:https://reurl.cc/D4EZoR

【活動聯絡】:盧小姐(naomilu613ann@gmail.com)

【講者】:Peter Baehr教授(Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa))

【主持】:梁啟智(本所訪問學人)

【時間】:2024年3月7日 14:00-16:00

【地點】:本所1009會議室(中研院人文社會科學館南棟10樓)

【報名連結】:https://reurl.cc/D4EZoR

【活動聯絡】:盧小姐(naomilu613ann@gmail.com)

※本場次演講以英語進行。

【講者簡介】

Professor Peter Baehr, Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa) / Former Chair Professor of Social Theory, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

【講者簡介】

Professor Peter Baehr, Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa) / Former Chair Professor of Social Theory, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

【演講簡介】

Why revisit a disastrous chapter of recent history? Rather than exhume the past, would it not be better, more respectful, just to give it a decent burial and then to leave it undisturbed thereafter? As stated, these questions are empty of content, germane to various sorts of enquiry: in moral and political philosophy, for instance, or in social theory or historical enquiry. In this essay I propose to consider the questions concretely. My subject is the defeat of Hong Kong’s democracy moment in 2020. My aim is to ask hard questions about this movement. My hope is that investigating these questions will bring greater understanding and clarity to the issues that they raise.

Here are some hard questions about Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Does it share blame or (if one prefers) share responsibility, for its rout? Paradoxically, did the emphasis on uniting the movement, and keeping it united, contribute to the movement’s defeat, especially when violence was allowed to flourish within its ranks as a legitimate tactic of protest? Was it sensible to encourage the United States to weigh in on the side of the democratic movement, thus introducing Great Power rivalry into an already fraught situation? Would any state – democratic or otherwise – have tolerated such massive disruption and violence as that unleashed in 2019, without moving to crush it at some point? What realistic good could ever come from the scorched earth doctrine known as laam caau (攬炒)? Might we conclude, with literary critic Frank Kermode (albeit in a different context) that “whatever devotes itself to justice at the expense of reality, is finally self-destructive”?

What good will asking hard questions do? Will revisiting the past help other people, years from now, do better in similar circumstances? Probably not: who can find a single scrap of evidence, anywhere, that one generation of protesters learns political lessons from its predecessors? Every generation learns what it learns, if it learns anything at all, from scratch. Underlying hard questions is a different conviction: that clarity through enquiry is better than evasion through timidity; that it is better to understand than not to understand; and that one does not understand anything complex without asking searching questions about it. And there is something more than understanding at stake. There is the desire to come to terms with reality: to reconcile oneself with events as they face us today, to see how “we” reached them, to settle accounts not with others but with oneself. This requires re-examining self-critically, the “terms” - the words, ideas, doctrines, frameworks - that defined one’s perspective and actions in the struggle. What did one not see and why did one not see it?

These are among the questions I address in this talk.

Why revisit a disastrous chapter of recent history? Rather than exhume the past, would it not be better, more respectful, just to give it a decent burial and then to leave it undisturbed thereafter? As stated, these questions are empty of content, germane to various sorts of enquiry: in moral and political philosophy, for instance, or in social theory or historical enquiry. In this essay I propose to consider the questions concretely. My subject is the defeat of Hong Kong’s democracy moment in 2020. My aim is to ask hard questions about this movement. My hope is that investigating these questions will bring greater understanding and clarity to the issues that they raise.

Here are some hard questions about Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Does it share blame or (if one prefers) share responsibility, for its rout? Paradoxically, did the emphasis on uniting the movement, and keeping it united, contribute to the movement’s defeat, especially when violence was allowed to flourish within its ranks as a legitimate tactic of protest? Was it sensible to encourage the United States to weigh in on the side of the democratic movement, thus introducing Great Power rivalry into an already fraught situation? Would any state – democratic or otherwise – have tolerated such massive disruption and violence as that unleashed in 2019, without moving to crush it at some point? What realistic good could ever come from the scorched earth doctrine known as laam caau (攬炒)? Might we conclude, with literary critic Frank Kermode (albeit in a different context) that “whatever devotes itself to justice at the expense of reality, is finally self-destructive”?

What good will asking hard questions do? Will revisiting the past help other people, years from now, do better in similar circumstances? Probably not: who can find a single scrap of evidence, anywhere, that one generation of protesters learns political lessons from its predecessors? Every generation learns what it learns, if it learns anything at all, from scratch. Underlying hard questions is a different conviction: that clarity through enquiry is better than evasion through timidity; that it is better to understand than not to understand; and that one does not understand anything complex without asking searching questions about it. And there is something more than understanding at stake. There is the desire to come to terms with reality: to reconcile oneself with events as they face us today, to see how “we” reached them, to settle accounts not with others but with oneself. This requires re-examining self-critically, the “terms” - the words, ideas, doctrines, frameworks - that defined one’s perspective and actions in the struggle. What did one not see and why did one not see it?

These are among the questions I address in this talk.

Topic: The laam caau doctrine: the sources from which it drew, and its resemblance and differences with other apocalyptical doctrines of mutual destruction

Speaker: Professor Peter Baehr (Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa))

Host: Leung, Kai-Chi (Visiting Scholars, Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica)

Time: 2024.03.07 (Thursday) 14:00-16:00

Venue: Room 1009, South Wing, Humanities and Social Sciences Building, Academia Sinica

Registration: https://reurl.cc/D4EZoR

Contact: Ms. Lu(naomilu613ann@gmail.com)

Note: This talk is presented in English.

Speaker:

Professor Peter Baehr, Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa) / Former Chair Professor of Social Theory, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

Brief:

Why revisit a disastrous chapter of recent history? Rather than exhume the past, would it not be better, more respectful, just to give it a decent burial and then to leave it undisturbed thereafter? As stated, these questions are empty of content, germane to various sorts of enquiry: in moral and political philosophy, for instance, or in social theory or historical enquiry. In this essay I propose to consider the questions concretely. My subject is the defeat of Hong Kong’s democracy moment in 2020. My aim is to ask hard questions about this movement. My hope is that investigating these questions will bring greater understanding and clarity to the issues that they raise.

Here are some hard questions about Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Does it share blame or (if one prefers) share responsibility, for its rout? Paradoxically, did the emphasis on uniting the movement, and keeping it united, contribute to the movement’s defeat, especially when violence was allowed to flourish within its ranks as a legitimate tactic of protest? Was it sensible to encourage the United States to weigh in on the side of the democratic movement, thus introducing Great Power rivalry into an already fraught situation? Would any state – democratic or otherwise – have tolerated such massive disruption and violence as that unleashed in 2019, without moving to crush it at some point? What realistic good could ever come from the scorched earth doctrine known as laam caau (攬炒)? Might we conclude, with literary critic Frank Kermode (albeit in a different context) that “whatever devotes itself to justice at the expense of reality, is finally self-destructive”?

What good will asking hard questions do? Will revisiting the past help other people, years from now, do better in similar circumstances? Probably not: who can find a single scrap of evidence, anywhere, that one generation of protesters learns political lessons from its predecessors? Every generation learns what it learns, if it learns anything at all, from scratch. Underlying hard questions is a different conviction: that clarity through enquiry is better than evasion through timidity; that it is better to understand than not to understand; and that one does not understand anything complex without asking searching questions about it. And there is something more than understanding at stake. There is the desire to come to terms with reality: to reconcile oneself with events as they face us today, to see how “we” reached them, to settle accounts not with others but with oneself. This requires re-examining self-critically, the “terms” - the words, ideas, doctrines, frameworks - that defined one’s perspective and actions in the struggle. What did one not see and why did one not see it?

These are among the questions I address in this talk.

Speaker: Professor Peter Baehr (Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa))

Host: Leung, Kai-Chi (Visiting Scholars, Institute of Sociology, Academia Sinica)

Time: 2024.03.07 (Thursday) 14:00-16:00

Venue: Room 1009, South Wing, Humanities and Social Sciences Building, Academia Sinica

Registration: https://reurl.cc/D4EZoR

Contact: Ms. Lu(naomilu613ann@gmail.com)

Note: This talk is presented in English.

Speaker:

Professor Peter Baehr, Fellow of the Center for Social and Political Thought, University of South Florida (Tampa) / Former Chair Professor of Social Theory, Lingnan University, Hong Kong

Brief:

Why revisit a disastrous chapter of recent history? Rather than exhume the past, would it not be better, more respectful, just to give it a decent burial and then to leave it undisturbed thereafter? As stated, these questions are empty of content, germane to various sorts of enquiry: in moral and political philosophy, for instance, or in social theory or historical enquiry. In this essay I propose to consider the questions concretely. My subject is the defeat of Hong Kong’s democracy moment in 2020. My aim is to ask hard questions about this movement. My hope is that investigating these questions will bring greater understanding and clarity to the issues that they raise.

Here are some hard questions about Hong Kong’s democracy movement. Does it share blame or (if one prefers) share responsibility, for its rout? Paradoxically, did the emphasis on uniting the movement, and keeping it united, contribute to the movement’s defeat, especially when violence was allowed to flourish within its ranks as a legitimate tactic of protest? Was it sensible to encourage the United States to weigh in on the side of the democratic movement, thus introducing Great Power rivalry into an already fraught situation? Would any state – democratic or otherwise – have tolerated such massive disruption and violence as that unleashed in 2019, without moving to crush it at some point? What realistic good could ever come from the scorched earth doctrine known as laam caau (攬炒)? Might we conclude, with literary critic Frank Kermode (albeit in a different context) that “whatever devotes itself to justice at the expense of reality, is finally self-destructive”?

What good will asking hard questions do? Will revisiting the past help other people, years from now, do better in similar circumstances? Probably not: who can find a single scrap of evidence, anywhere, that one generation of protesters learns political lessons from its predecessors? Every generation learns what it learns, if it learns anything at all, from scratch. Underlying hard questions is a different conviction: that clarity through enquiry is better than evasion through timidity; that it is better to understand than not to understand; and that one does not understand anything complex without asking searching questions about it. And there is something more than understanding at stake. There is the desire to come to terms with reality: to reconcile oneself with events as they face us today, to see how “we” reached them, to settle accounts not with others but with oneself. This requires re-examining self-critically, the “terms” - the words, ideas, doctrines, frameworks - that defined one’s perspective and actions in the struggle. What did one not see and why did one not see it?

These are among the questions I address in this talk.